Oral Traditions

The ancient faith of Zoroastrianism survived through oral traditions for millennia. When Alexander of Macedonia burnt Persepolis, the community records were destroyed, and when Persia was conquered by the Arabs and the Mongols, the former State Religion was reduced to a handful of refugees fleeing either into the desert regions of Yazd and Kerman in Iran or seeking freedom to practice their faith in India. Despite the shifts and breaks in the community records, this culture's survival from the Bronze Age has relied heavily on the powers of Oral transmission.

Two primary aspects of the culture have been passed on through the Oral Tradition. The first is the simplest distinguishing feature of every practicing Zoroastrian- the use of the garments of the sudreh and kusti. (link section) The second is an examination of the Yasna (link section) - an ancient, almost prehistoric ceremony. Through the oral tradition and later textual evidence, both rituals, of the sudreh-kusti and yasna, interlink to create the living foundations of a faith.

The Gathas, oral songs or hymns, have been carefully preserved in memory as the most sacred part of the Avesta, the words of Prophet Zarathushtra himself. They are arranged in five formal groups according to their various metres and were made part of the daily liturgy called the Yasna or ‘act of worship’. The Younger Avestan Yasna grew to have seventy-two sections, some parts of which were taken from the Yashts or hymns to the lesser divinities of Zoroastrianism. A later addition to the scripture is the Vendidad (Vidaevo-data, ‘against the demons’), a collection of prose texts in the late Younger Avestan probably started in the Parthian period and concerned with rituals and observances against evil. This became a part of the night celebration of the Yasna, and is the only text not recited entirely from memory.

The book most commonly used as a Book of Daily Prayer is the Khordeh or “little” Avesta, a compilation of prayers for everyday use made from the main texts. Until the nineteenth century, Zoroastrians learnt their prayers by heart, but ever since, the Khordeh Avesta has been used. A great collection of all the Zoroastrian prayers was the Sasanian Great Avesta, committed to writing in the 5th-6th centuries AD. Because of the ravages caused when most Fire Temples were destroyed, not a single copy of this book now exists. It survives however through a detailed summary given in a later 9th century Pahlavi work called the Denkart or “Acts of Religion”. Zadspram, a priest of the 9th century AD compiled these selections along with details of the life of Zarathushtra. From this book we see that the extant texts are only a quarter of the entire Zoroastrian canon. The prayers have survived mainly because they were in constant use and recited by heart.

Monajats

In Zoroastrian prayers while the Nirang continued the tradition of a manthra being recited for the inherent power of its words, another type of prayer which reflected a personal communion with God was the monajat. The term itself derives from an Arabic word approximately meaning ‘intimate conversation (with God), prayer’. While the older Khordeh Avesta contained monajats which were popular in both the Parsi and Iranian Zoroastrian communities, they have been almost completely forgotten in the linguistic losses which have faced these communities in the 20th century.

Monajats were in the spoken language of the believer: it could be Persian or Gujarati and they were chanted or sung. Many were songs of praise, prayers to thank the Almighty, women’s songs and lullabies which included blessings on a child going to bed or requests for blessings on family members. Some were for special occasions such as marriages and Navjotes, mingling in India with the tradition of the Geet and Garba, songs and dances, for family and social events. With the loss of the spoken dialect P.G., these songs have almost disappeared.

The best example of P.G. is perhaps in the monajats, which need to be studied in detail, because they have kept for the Parsis, for over a thousand years, the memory of their Zoroastrian culture.

The monajat is the simplest form of Zoroastrian oral transmission. Learnt in childhood, when children pick up monajats as a fun filled part of the day, it becomes the oral equivalent of cultural transmission even before a child has learnt to read. It has no teacher or priestly guide. It is a family centered transmission, a very informal system which children absorbed almost by osmosis and binding everyone together in music.

It is through the monajat that core teachings entered a child’s consciousness to reinforce living precepts and examples. While these songs are very simple, they show how a tradition and religion transmits itself. Important Avestan words, concepts from the Gathas, a very complex set of teaching have been carried across millennia through Persian and Parsi Gujarati monajats.

Traditionally sung in Gujarat while evening fell and generations gathered around the swing on the verandah, monajats now need to be taught in Sunday classes where other aspects of the faith and culture are inculcated;

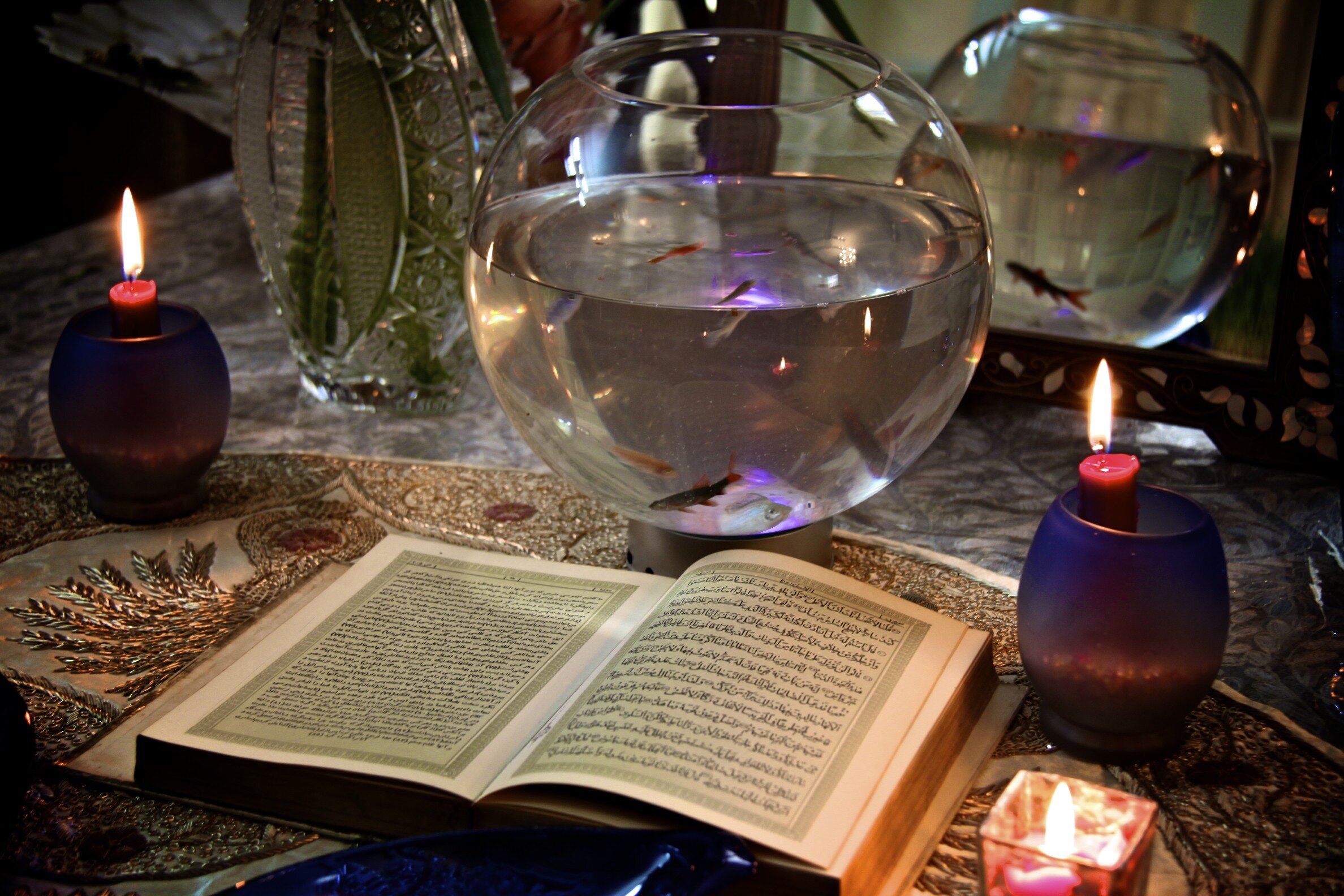

Image 1 - Ahmedabad, the late Khorshed Dastoor teaches her granddaughter Delnaz Jokhi;

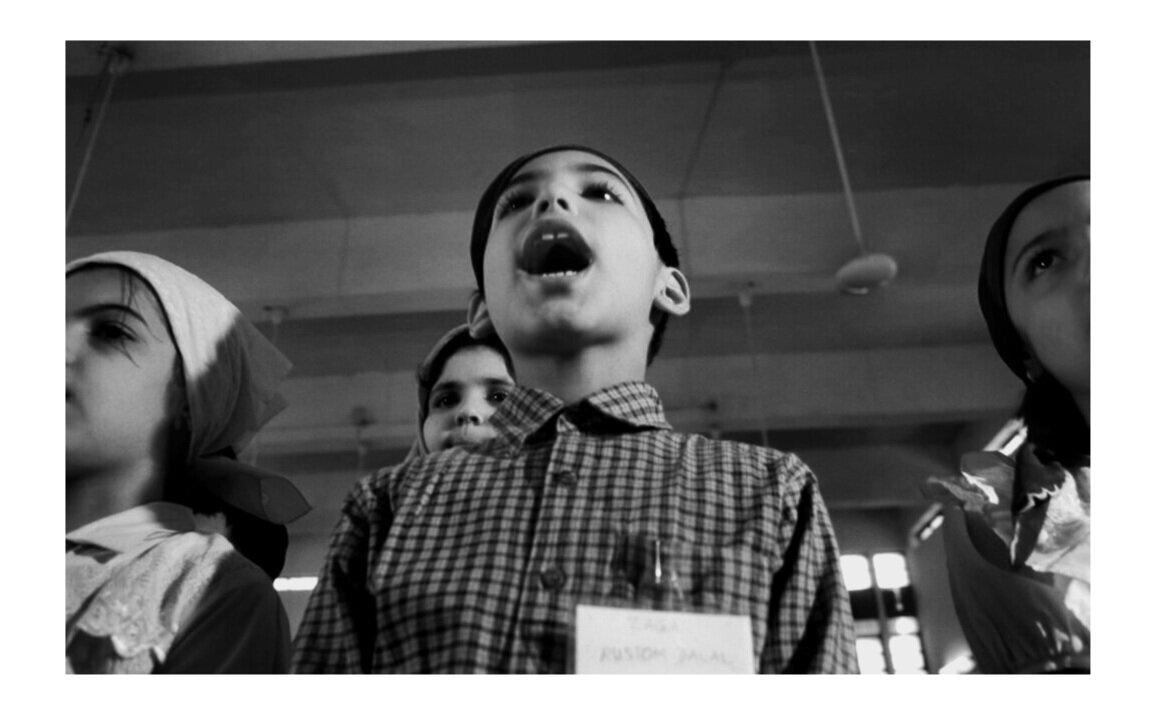

Image 2- students at the Ushta-te classes, Ahmedabad.

Monajats in Avestan, Persian and old Gujarati. There are altogether five monajats in Persian with zend characters, avestan and old Gujarati. Presented by Dastur Rustomji Kekobadji Dastur Meherjirana. Meherjirana Library, Navsari

Related Articles